What is AI Reasoning “Text” and Why It’s Not What You Think

This post is a concise, adapted version of the paper "State over Tokens: Characterizing the Role of Reasoning Tokens" written by Mosh Levy, Zohar Elyoseph, Shauli Ravfogel, and Yoav Goldberg. For the full paper, see https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.12777.

One of the most captivating features of recent chatbot models is how transparent they seem when they "think" out loud, generating step-by-step text before their answer. This might suggest we can trust them because we can check their logic, but growing evidence shows this is an illusion. The text looks like a human explanation, but it functions as something fundamentally different: a computational mechanism we suggest calling State over Tokens. Treating this mechanical state as a plain-English account of reasoning is a mix-up—one that risks undermining AI safety, regulation, and public trust. This post explains what this "text" actually is, and why it doesn't do what you think it does.

The Vacuum Beyond the Explanation Illusion

Large language models produce better answers to reasoning questions—math, logic, complex problem-solving—when they generate text (often called “reasoning tokens”) before stating their final answer. People have observed this across different systems, and it seems to be part of how these models work. If you’ve used a recent chatbot for a challenging problem, you’ve maybe seen this “thinking”: the system generates text with phrases like “First, let me consider…” or “Wait, I need to reconsider this approach…” This text uses first-person language, logical connectors, even apparent self-correction. It reads like human reasoning put into words.

This appearance makes a natural interpretation tempting: that we are seeing a play-by-play of the model’s internal process—a window into how it reached the answer. The metaphor often used to describe it, “Chain-of-Thought” [1], strengthens this impression, suggesting the text reveals the model’s chain of reasoning.

But a growing body of research shows that this impression can be an illusion. Research shows this in a few ways. Models omit critical factors that actually influenced their answers [2,3,4,5,6]. Models can arrive at correct answers while producing nonsensical or irrelevant text [7,8,9,10]. And, in our previous work we showed that humans cannot reliably predict the actual relations between steps in the text [11] (see the interactive demo at do-you-understand-ai.com). Together, these findings show that even when the text appears convincing and logical, it may misrepresent the actual reasoning process the model followed.

But if the text does not reliably explain how the answer was produced, what is it doing? What is its role in improving the performance of LLMs? This leaves a vacuum: we know how not to think of this text, but we lack a clear way to describe what it actually is. We believe that without better language for it, it is harder to fully shake the explanation illusion or to surface new questions about this text.

In this post, we look at how LLMs generate tokens and offer a simple way to think about it—State over Tokens—that supplies this missing language. We use it to clear up common misconceptions about step-by-step text and to open up new ways of thinking about its role and implications.

The Whiteboard Thought Experiment

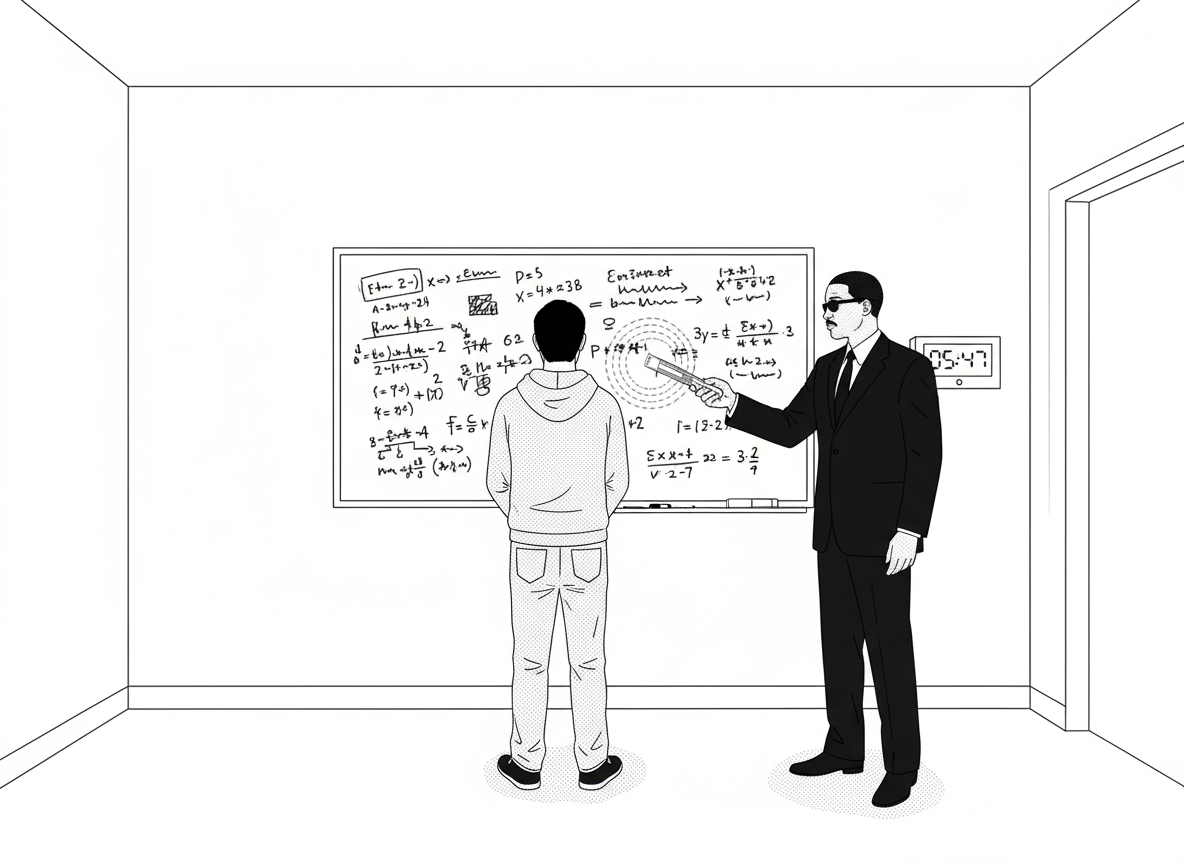

Imagine being in a room with a whiteboard showing a problem—say, a complex math problem. You’re told upfront about a peculiar constraint: every 10 seconds, your memory will completely reset. Everything you figure out will vanish. You’ll forget you even looked at the problem. The only thing that will persist is what’s written on the whiteboard. In each 10-second cycle, you can add a single word to the board before your memory wipes.

Knowing this, how would you solve the problem? The text on the whiteboard becomes your only lifeline. When you “wake up” each cycle, you read the board to understand where you left off. During those 10 seconds, you might do substantial mental work—exploring approaches, weighing options, running calculations. But you can leave behind only one word to help your future self continue the process. This constraint shapes what gets written.

You might perform several mental calculations before writing down just the key result—so the whiteboard won’t capture every calculation you did. Maybe you write a crucial number, a pivotal insight, or a reminder. You might also use personal shorthand: abbreviations, symbols, or codes that mean something specific to you but look cryptic to outsiders.

Someone watching from outside the room might completely misunderstand what’s written. They might see “CHECK” and assume it means “check the previous step,” when actually that word functions as a private marker—perhaps indicating where to resume after verifying intermediate results. They might see a series of numbers without realizing they encode information that has nothing to do with the question in their direct meaning.

This thought experiment is a useful way to picture how LLMs use language to reason. The problem is the user input. The words on the whiteboard are the “reasoning tokens” (the technical term for the pieces of text the model generates), the memory wipe after each word reflects that the model doesn’t maintain internal state between words except for these tokens. The 10 seconds of thinking time corresponds to the model’s computational capacity when generating each word.

It’s natural to imagine that chatbots think continuously while producing text, but under the hood, the LLM generates each token (~word) in a separate, stateless burst of computation. Unlike humans, LLMs have no persistent memory across the generation of each word. When the model generates the next word, it doesn’t “remember” what it was “thinking” when it produced the previous word. Instead, it makes a computation based solely on the input prompt and the text generated so far. This computation is substantial (involving billions of calculations), but it’s fundamentally limited. The model can’t “think longer” to produce a harder word. This makes the text not just helpful, but essential: it’s the sole carrier of information from one step to the next; the model has no separate, introspective workspace. (Technical note: current implementations do store intermediate computations via KV cache, but only as an optimization — the stored information is fully reconstructible from the tokens.)

Introducing State over Tokens

So what is that text actually doing? From the whiteboard story, we see how it is a tool for the future self—the version that will wake up after the next memory wipe with no memory of what just happened. The tokens help the model by doing one job: to encode the progress made in this cycle in a way that allows the future self to continue the process.

Like what’s written on the whiteboard, the tokens play the role of what computer scientists call “state”: the information that captures where a process currently stands and helps determine what happens next. This is an unusual form of state: encoded in language and updated with the addition of one token per cycle.

We offer to call this phenomenon State over Tokens (SoT). This perspective shifts how we think about the text: not as explanation to be read, but as state to be decoded.

We now use this framework to break down the explanation illusion and then explore questions about this text that are easy to miss. (See the full paper for more implications of our framework.)

Unpacking the Explanation Illusion

We believe the illusion that the text is an explanation rests on two misconceptions. Using the State over Tokens framework, we now unpack both.

Misconception 1: “The text shows all the work”

Return to the whiteboard room. The problem: “What is the 9th Fibonacci number?” You know the pattern: each number is the sum of the two previous ones. With your repeating memory wipes and one-word-per-cycle constraint, you proceed. After reading the problem, you write “1”. Memory wipes. You wake up, read the board, write another “1”. Memory wipes. You wake up again, see two 1s, compute their sum, write “2”. And so on. Eventually, the board shows: 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34.

These numbers are crucial—you can’t arrive at 34 without building through the earlier ones. But does this sequence explain the work in each cycle? Does it show the mental arithmetic, the checking, the brief confusion when your memory first wiped? No. The board shows intermediate results, not the process. It’s like mistaking the scaffolding for a building. The scaffolding is essential—you can’t build without it—but it’s not the actual construction.

In each cycle, you do invisible work—exploring possibilities, running calculations, weighing options. But you can only leave behind a compressed summary: a single number. The same applies to LLMs. The text shows results that enable the next step—scaffolding that lets the process continue—but it doesn’t have to show the actual computation. We see what the model left for itself, not necessarily how it got there.

Misconception 2: “The words mean what they appear to mean”

Even if we accept that the whiteboard shows only partial results, we might still assume that outside observers trying to understand your process by reading the board would interpret what appears there the same way you do—and maybe connect the dots to figure out your considerations and calculations. But this assumption is also mistaken.

Imagine the observer sees you write: 11, 11, 12, 13, 15, 18, 23, 31, 44. These aren’t Fibonacci numbers at all.

Here’s what’s happening: you’ve developed a personal encoding scheme. When you wake up each cycle, you read each number, subtract 10, then use the real values to compute the next Fibonacci number. Before writing it down, you add 10. So when the board says “11, 11, 12, 13, 15, 18, 23, 31, 44” you internally decode it as “1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34” and use those values for your computation. At the final step, you subtract 10 and report the true answer: 34.

This encoding is arbitrary. The surface appearance can completely mislead outside observers trying to understand what you did. But it works perfectly for you. Future-you knows the system: decode, compute, encode, write. Why might you do this? Perhaps it’s a quirk that emerged early and became a habit. Or perhaps when you first entered the room, you noticed the number 11 on the door—and when it came time to write down the first real Fibonacci number (1), you wrote 11 instead, following that association. Or perhaps adding 10 during calculations is something that just feels familiar and reliable to you so you do it. Or perhaps your instructions for producing the 9th Fibonacci number explicitly prohibited writing the Fibonacci sequence on the board, so you chose an encoding that hides it on the surface while keeping it usable for your process. The encoding might have stuck not because of logical necessity, but because it works for you. Existing work on how models can embed information in ways that are hard for humans to detect suggests that real-world encodings can be much more complex than this toy example [12]. The point is simple: what appears on the board may look wrong to observers trying to interpret your process while being perfectly functional for you—the numbers do not mean what they appear to mean.

Now extend this to language. When the model writes “I need to reconsider this approach,” what does that phrase actually do? It might genuinely represent a self-check. But it also might encode something entirely different. Perhaps in the model’s internal “dictionary,” that phrase functions as a marker meaning “branch point ahead” or “store current assumption for later verification”—something that doesn’t match any familiar human mental move. The model writes for itself on its computational whiteboard, potentially using its own encoding system. A phrase that looks meaningful in English might function differently in the model’s process. And a phrase that looks like gibberish to us might be meaningful to the model—encoded in a way we don’t naturally interpret.

This may explain why researchers found that models can produce apparent nonsense and still get correct answers. The text wasn’t nonsense to the model—it was encoded state on its whiteboard. It was only nonsense when read with standard English semantics; we just couldn’t read the encoding.

Why Does It Look Like English?

If these tokens mainly function as state for the model’s process, why do they read like ordinary English? There can be many explanations for that. One possible explanation is that these models are trained on massive amounts of English text. When they generate any tokens—whether it’s an answer to a user or intermediate tokens for their own process—they use the patterns and structures they learned during training. (See the full paper for more discussion on this.)

The same tokens exist as two fundamentally different kinds of things: for human readers, the tokens are text; for the model, the tokens are state. The fact that it reads like coherent English encourages us to interpret it as a transparent explanation, when what matters for the model may be something other than what the words appear to say.

What This Means Going Forward

Thinking of the tokens as a state mechanism encoded in language makes the practical implications clearer. We believe that this framing matters for anyone using, building, or thinking about AI systems.

For anyone using AI systems

Don’t assume the text explains how the model arrived at its answer. The text might increase confidence without providing real justification. This matters especially in high-stakes domains like medicine, law, or finance.

Sometimes, the text will happen to present a valid sequence of steps from question to answer. If you carefully check each step and confirm that the logic holds, it can serve as supporting evidence for trusting the answer. But this confidence should come from your verification, not from the text itself being a direct view into the model’s process.

For AI researchers and developers

This perspective suggests a different way to study the text. Instead of reading it as plain English and assuming we understand what’s happening, we argue that we need to decode it—similar to decoding a compressed file format or reverse-engineering a protocol.

This opens research questions: How do models decide what information to encode at each step? Do they use consistent encoding schemes across different problems? What information is actually embedded in the state at different points? How does information propagate through the sequence?

There’s also a deeper question: Is language special for this purpose? Human language has many years of evolutionary optimization—does something about its structure make it particularly good for encoding computational state? Or could models use other media equally well? Some researchers are exploring alternatives, but whether language has unique advantages remains unclear.

And perhaps most ambitiously: Could we ever get text that serves both purposes—functioning as computational state for the model and providing faithful explanations to humans? This framework clarifies why that’s difficult: it requires the model to simultaneously perform computation and describe that computation through the same medium. But understanding the challenge is a necessary first step.

The Takeaway

Much discussion about LLMs reasoning abilities focuses on what the text isn’t. But criticism alone leaves a vacuum. If it’s not an explanation, what is it?

State over Tokens: computational state encoded in the token sequence—a functional tool the model creates for itself to maintain a process across multiple steps of limited computation. Not a transparent window into the model’s reasoning process in English terms, but the scaffolding that enables the process to happen at all.

This matters for building more reliable AI systems: understanding the functional role of these tokens might help us design better architectures that use this scaffolding effectively. It matters for responsible deployment: we need to set trust based on what the text actually does, not what it appears to say. Systems that generate elaborate text might not be more trustworthy than systems that don’t—we still need real-world validation rather than accepting the apparent rigor.

For those of us who care about AI risk and AI safety, it provides another reason not to take the text produced by the model at face value, and instead invest more effort in methods that probe the actual computations the model runs.

Understanding State over Tokens doesn’t solve all mysteries. But it moves us from criticism to positive characterization—from “it’s not what it looks like” to “here’s what it actually does.” We believe that shift provides a foundation for better interpretability methods and clearer thinking about what AI can and cannot do.

Full paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.12777

References

[1] Wei, J. et al. (2022). "Chain-of-thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models." Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems.

[2] Turpin, M. et al. (2023). "Language Models Don't Always Say What They Think: Unfaithful Explanations in Chain-of-Thought Prompting." Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems.

[3] Yee, E. et al. (2024). "Dissociation of faithful and unfaithful reasoning in LLMs." arXiv:2405.15092.

[4] Chua, J. & Evans, O. (2025). "Are DeepSeek R1 and other reasoning models more faithful?" arXiv:2501.08156.

[5] Arcuschin, I. et al. (2025). "Chain-of-thought reasoning in the wild is not always faithful." arXiv:2503.08679.

[6] Marioriyad, A. et al. (2025). "Unspoken Hints: Accuracy Without Acknowledgement in LLM Reasoning." arXiv:2509.26041.

[7] Lanham, T. et al. (2023). "Measuring Faithfulness in Chain-of-Thought Reasoning." arXiv:2307.13702.

[8] Chen, Y. et al. (2025). "Reasoning Models Don't Always Say What They Think." arXiv:2505.05410.

[9] Stechly, K. et al. (2025). "Beyond Semantics: The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Reasonless Intermediate Tokens." arXiv:2505.13775.

[10] Bhambri, S. et al. (2025). "Interpretable Traces, Unexpected Outcomes: Investigating the Disconnect in Trace-Based Knowledge Distillation." arXiv:2505.13792.

[11] Levy, M., Elyoseph, Z., & Goldberg, Y. (2025). "Humans Perceive Wrong Narratives from AI Reasoning Texts." arXiv:2508.16599.

[12] Cloud, A. et al. (2025). "Subliminal Learning: Language models transmit behavioral traits via hidden signals in data." arXiv:2507.14805.